From the book: Le Rona Re Batho (An account of the 1982 Maseru Massacre) by Phyllis Naidoo, South Africa, 1992

Exiles who sought political asylum from the regime’s racist policies and its total repression of human rights activists, after June 1976, arrived in Lesotho in droves. By 1977 it was around 10-15 persons arriving daily. They were mainly the youth, some as young as 10 years. They were interspersed with ex-Robben Islanders, for whom punishment extended beyond the prison cells, with not a day of remission of their sentences. On release they were restricted and banned under the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950. Some were banished away from their homes to the repression of the homelands where jobs were few. Homeland regimes in impoverished tribal areas, discourÂaged employers from employing them and further detention and harassment followed them.

Despite the pain of being parted from family and friends, refugees coming to Lesotho found a freedom here, not had at home. Students who went to school did not have Bantu EducaÂtion even though at times the constraints of a poor country having to sustain its own educational needs were felt. But Lesotho shared her meagre resources so generously with us.

South African refugees could now read most of the books banned in their own country. Some ‘met’ Nelson Mandela in exile for the first time. He had been in prison since 1962. His “NO EASY WALK TO FREEDOM” was their first reading. They read hungrily.

They staged a play of Oom Nel at his trial (1962), and could recite with ease, his statement to the court and compared it to Castro’s historical speech at his own trial – “HISTORY WILL ABSOLVE ME”.

My Basotho clients complained that these South Africans wore perky hats and read all the time. Why? When I explained why that was so, no not the hat, but the reading, they were duly shocked at the censorship laws of our country.

They left behind the trauma and pain of the DOMPASS. The 11 pm curfew which sent Blacks scuttling away from the streets to avoid arrest was lost in their newfound freedom.

Some students whose burning complaint had been the compulsory imposition of Afrikaans in schools found, in exile, Sesotho, the local language, a problem if they were not Sotho or Tswana speaking. Many had no problem at all and were at home with the language.

“Here, however, their lingua franca strangely was mostly AFRIKAANS. When they met in the streets or visited friends it was AFRIKAANS they spoke. Don’t ask me why.

Sesotho, surrounded by Afrikaans speaking neighbours in the Orange Free State and the northern Cape, had incorporated many Afrikaans words into its language. One that comes to mind is AGENTE = lawyer. Also, wait for it, there in the heart of Lesotho was a Dutch Reformed Church. Yes, the same church which gave to apartheid its biblical authority and to the liberation struggle Rev Alan Boesak.

Exiles in Lesotho also found a complete absence of tribalism. In fact, we brought this with us into their society with our baggage of apartheid. They were all Basotho, one nation speaking one language.

I was told that to the south, near Qachas Nek (NB. Nek is an Afrikaans word for NECK. You would have expected this ex- British colony to be properly English.) Which borders Xhosa speaking Transkei, language and norms are duly affected, but the language is Sesotho.

A young student from the Eastern Cape, Gwendun, is seeking political asylum, crossed the river, (no, no river in Lesotho has seen a crocodile) into Lesotho near Qachas Nek and boarded a bus.

Comrade Gwenduna Murdered near Lesotho

Comrade Gwenduna Murdered near Lesotho

He had decided not to talk to anyone on the bus as this would reveal he was not a Mosotho. So he took out his newspaper and was intent on reading it. His attention was drawn to a passenÂger looking intently at his newspaper. In fact, he bent over to read it.

Bound to his self-imposed silence, he returned to the newspaper to find out what had intrigued his neighbour. To his horror he found he was reading the paper upside down.

Fortunately we Blacks do not show red/pink embarrassment, he handed the paper to his neighbour and looked pointedly at the view outside the window.

Gwenduna, too, years later was brutally killed at the same border. So much youth, with so much caring concern for our country lie in those bones. Hamba Kahle Gwenduna.

Lesotho, this impoverished, stark country opened its arms in welcome to us. What did Lesotho have to offer? Tourists, of course, are fascinated with its mountains.

They come to yearly motor rallys. They go to mountain lodges. They come to gamble at the casinos and to see Blue films denied to them in South Africa. White South Africans came to Lesotho to escape the rigours of the Immorality Act.

When Britain handed over the reins of Government to the new Lesotho government in 1966, with due pomp and cerÂemony, it left behind a racially separated watering hole at the Lancers Inn and the only piece of macadamised road from the British High Commissioner’s house to his office. Chief Jonathan had to start with a clean slate.

The only jobs available to youth entering the job market were in teaching, the church, and the mines and with British rule, the civil service.

Teaching paid 2 pounds and ten shillings a month. The church paid whatever could be collected from poor parishionÂers per month. The mines paid 3 pounds. Mr. Motsamai who gave me these figures was about 67 years old in 1977. So these figures relate to the position 47 years previously, i.e. around 1930.

They’re being no choice at all, he went to the mines after trying for years to do something else. The medical examination that kept him nude for two days put paid to a mining career. He said in so much pain, ” I could not bear to be nude in the presence of the youth”.

He taught and later went into the civil service.

The British colonial retirement age of 45 was also imposed on the locals. However no locals were entitled to pensions and unless they had employment or arable land/ an early death was their, only escape.

Another aspect of Lesotho is the Roman Catholic Church. It is a powerful, all pervasive institution in the mountain kingdom. Many Basotho have embraced the church and its language to understand better their imperial masters. The church lent its support to the ruling party (BNP) in the first elections ushering Lesotho’s independence. I was told by man the local priest knew a communicant was a BCP men would pass his open mouth for the next mouth. Their newspaper, Moeletsi Wa Basotho, is popular reading in Catholic circles. Anti-communism was to it, what apartheid is to South Africa.

Like South Africa which objected to the Soviet Embassy being sited in Maseru, the church too was extremely vocal on the issue. The paranoia of the South African government to the visit of three puny Cubans was equally matched in Moeletsi Wa Basotho.

In most countries, next to the government in power, the greatest landowner is the Catholic Church. Rumour has it in Lesotho that the Catholic Church far outstrips the government of the day in land usage.

It has schools all over the country, sometimes in inaccessible places high on the mountains with commanding views and where an aeroplane is the only means of transport. It established the University of Lesotho – ROMA COLLEGE, and later handed it to the newly independent government reserving for itself some strategic rights. It has beautiful churches dotted all over the country built out of the indigenous stones. Talking about confessions to a colleague he told this story. In parts of Lesotho, for penance after confession, the priest imposed, not the usual, 10 Our Fathers and 10 Hail Marys, but 20 wheelbarrow loads of sand from the nearby river! Confession built our churches.

Some founding fathers came as from far afield as Canada. Prime Minister Jonathan was awarded his doctorate from Canada as well. Naturally the church was constrained to attract local support for its continued existence. Seminaries are available to those Catholics who wish to become priests. Convents for nuns are available for Basotho women who wish to serve the church. Some Basotho went to Catholic schools, seminary and Roma College and then changed from canon law to the laws of the land. Some are in the judicial system in Lesotho. Some nuns have been known to change their minds at university and take marriage vows for ordinary mortals, their colleagues.

The other area in which the Catholic Church lent its expertise was in health. It has clinics and hospitals all over the country and provided this service to the colonial government as well as independent Lesotho. The health resources that an impoverÂished Lesotho could provide were minimal. After the South African sponsored coup which toppled Chief Jonathan in January 1986, the SADF built a hospital for Lesotho’s paramiliÂtary unit. The health needs of Lesotho are indeed acute.

Other Christian churches exist, some with similar supports to the national life of Lesotho in both health and education. One gave us Canon John Osmers, Father Michael Lapsley and some caring people on a little mount in Masite. The barefooted nuns in Masite are superhuman beings.

The land surface is mostly rock. Sixty percent (60 %) of its surface is stone and is the home of the goat that provides mohair for its limited industry which is controlled by South Africa. Young Basotho children, fondly called herdboys, tend the cattle and goats at different cattle posts in the mountains. Their formal education is neglected, their loneliness from home compounded by the bitterly cold winters with ONLY tattered blankets covering their emaciated bodies for protection. One, Helen Brauer of IVS, International Voluntary Service (UK), organised their learning under an UNICEF programme and became their friend. She was a very special person and gave them her talent, her love and so much of her time.

‘Herdboys’ are also the butt end of lightning storms. Their dead bodies tell of the danger that stalks them in the mountains.

The 40% arable land caters for both habitation and agriculÂture. The rivers and storms due to the nature of the terrain and overgrazing carry much of the soil away. Agriculture is limited. You cannot separate the Basotho from their cattle. Even a Minister of State kept them at the back of his home in Maseru West, the home of the Basotho elite and the diplomatic corps.

White South African farmers ‘assist’ with tractors, seeds and fertilisers at a price that increases the Basotho farmer’s indebtÂedness and reduces them to the status of unpaid servants.

Very few Basotho nationals control trade and commerce in their country. These concerns are in the hands of South African conglomerates that have located their stores in the middle Maseru etc. A big store in South Africa would counterpart in Lesotho.

On its 12 borders, it has towns on the South African side where every service is found. Why set up a motor repair shop in Lesotho when it can be done cheaply in the border town. When the price of housing rocketed in Maseru people could stay in Ladybrand cheaply. But those who opposed apartheid would not and could not.

The only area of work that embraces a few hundred Basotho is the civil service, police and the army. It is the biggest industry. This is paid for by taxes, the customs union and certain machinations of miners wages arrived at mining houses.

As a legal practitioner, I met many a client who had been inflicted with miner’s pthisis (TB) and were sent home without any support. No pension. With a Mosotho name South Africans, journeying into Lesotho, obtained the good services of a chief with a similar name and were given a piece of land such luck in apartheid South Africa, the land of his birth.

They found a home here. Pensioned workers, v their pension in one fell swoop, came across and invested in a home, a butcher’s shop or vegetable stand. So there was a vast array of South Africans ‘exiled’ in Lesotho, not seeking the assistance of the UNHCR.

In the late fifties, Anderson Khanyile and Elizabeth Mafekeng sought shelter here from banishment. With the emergency in South Africa in 1960, many South Africans, after the massacre at Sharpeville, sought refuge in Lesotho – both ANC and PAC supporters. Khalaki Sello was imprisoned for two years for membership of the ANC, etc. He escaped to Lesotho was placed under house arrest on his release from 1967. Luckily for him his home was in Lesotho and he was able to establish an identity and a legal practice.

With the repression that followed the massacres 16 June 1976, droves of children and South African agents Swaziland, Botswana and Lesotho.

Lesotho, the poorest of the three, historically re its hospitality to refugees, welcomed this added burden. Government figures gave the figure of 10 000 refugees, I certainly agree with that figure as most of the aforementioned did not register with the UN agencies. In fact if my memory at all the accords with the UN were signed in 1978,

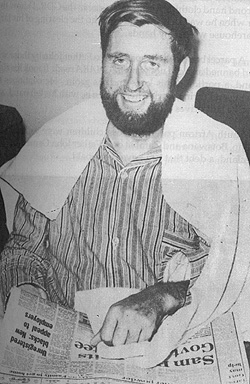

Comrade Father John in Queen 2 Hospital on 6 July 1979, recovering after the bomb attack on 5 July 1979

Comrade Father John in Queen 2 Hospital on 6 July 1979, recovering after the bomb attack on 5 July 1979

Lesotho was assisted with schools and laboratories but nothing to compensate the financial burden we placed on this fragile mountain kingdom.

The Department of Interior (Home Affairs) created a departÂment headed by Mr. Mokhele to cater for our various needs. Dealing with so many township youth was a new experience for him. He was very British in his approach and stuck to the letter of the law, enjoying his power over us. He was always courteous to me, even though he did not understand an Indian’ refugee from South Africa. “You could have a Mercedes Benz,” he argued.

Oppressed we might be but we came from a highly indusÂtrialised, high tech society. We may have been denied much but we were aware of much more. When a lift was installed into a new block of offices in which the government’s Legal Aid facility operated, poor Basotho who had never been out of their country found difficulty in using the lift. Women sat down on the floor, one urinated when a young refugee happened to be in a lift with us. The young man laughed uncontrollably while I sought to help the woman. Despite my scolding he could stop laughing at the sight of a woman fearful of a woman fearful of a lift.

These were children brutalised by apartheid who stood to their torturers and many of whom were killed for it. Their tolerance level to authority was minimal. It took much selling by the ANC to help the youth in exile. Young children in the care of both their parents in normal homes are beset with ordinary problems of growing up. How much more when so many of our brutalised youth were far removed from family loved ones and a familiar environment?

Canon John Osmers gave his home, telephone and meagre food supplies to all of us. His little van carried young refugees around Maseru. He remembered their birthdays, took them to the hospital when ill and took them blankets and a warm them in winter. He arranged the all vigil yearly on the night vigil the night of 16 June. He would find the coffee and sandwiches for the long night. He took our traumatised children to stay with him at Masite. When the ANC organised UMPANDO, Fr. John had obtained a shipload of second hand clothing from a colleague in the GDR. I know this, for when he was kicked out of Lesotho the clearing of HIS LARGE warehouse was in my hands.

Who is a Mosotho

Who is a Mosotho

A parcel bomb was despatched to Father John by those who had banned and did not want SECHABA read. It took his right, hand a portion of his knee and his groin. He continues his loving and caring work wherever he is, with his left hand, and yes, he still drives a van.

South African parents whose children were exiled in Lesotho, Botswana and Zambia owe Father John Osmers of New Zealand, a debt that can never be repaid.